'Jesus is light for those who dwell in darkness. He is hope for us – in our personal lives, in our life in the world, for humanity as a whole.'

The Third Sunday after the Epiphany

January 22, 2023

The Rev. Maurice C. Frontz III

St Stephen Lutheran Church

Some of us will vaguely know what the

‘Enlightenment’ is. According to Brittanica.com, the Enlightenment was ‘a European intellectual movement of the

17th and 18th centuries in which ideas concerning God, reason, nature, and

humanity were synthesized into a worldview that gained wide assent in the West

and that instigated revolutionary developments in art, philosophy, and politics. Central to Enlightenment thought were the use

and celebration of reason, the power by which humans understand the universe and

improve their own condition. The goals of rational humanity were considered to

be knowledge, freedom, and happiness.’

Clear as

mud, right? But they tried. Let’s give a couple of examples, though. We are

beneficiaries of much that came out of the time of the Enlightenment. From the

Enlightenment sprang the scientific method we all learned in school:

observation, hypothesis, experiment, analysis, conclusion. This approach has

led to many of the advances that humanity has made in the fields of technology

and medicine, for example; changes that have made our lifespans longer and less

difficult day-to-day.

We also owe

our system of government to the Enlightenment. By the power of reason the

philosophers upon whom the American Founders relied deduced that government

existed for the people, not people for the government, and that when government

did not work for the people’s benefit, the people had the right to consent to a

different system, one which would protect their God-given rights. Which rights

those are and how far they extend, those have been a matter of debate since the

beginning of our Republic. But at least we can have those debates among

ourselves.

Reason,

science, liberty: All of these are words we associate with the European

Enlightenment. But, as I just mentioned, human beings, using reason, come to

different conclusions about truth and knowledge. People in power believed that

they could direct human affairs towards order and goodness according to reason,

only to be confused by the messiness of life and the desire of the human heart

for liberty. Using the tools of experimental research bequeathed to them by the

Enlightenment, scientists not only created life-saving medicine but

life-destroying weapons. The French Revolutionaries, having dethroned God and

set wisdom in His place, ended their reasonable revolution by executing any and

all who were opposed to them. The Enlightenment has been a mixed blessing at

best.

Why talk

about this at all? It is because the Enlightenment was and is seen as first and

foremost a source of hope. For we are all looking for hope: for our own health,

safety, and flourishing; for the well-being of the world; for the future of

humanity and its planet.

The people

of the Enlightenment believed that if they applied reason, they might solve the

problems of life and lead humanity into a new age of the world. They may have

solved some problems, but others sprang up in their place or proved intractable.

Other people

have similar hope for an ‘enlightenment.’ In the days of the 60s, the flower

children believed that in rejecting the values and morals of a conformist

society, they were bringing a new age into being. I think we’re still waiting.

The Internet age began with people who believed that by making information free

and communication instant, we would live in a ‘global village’ which would make

conflict less likely and people happier. Didn’t really work out that way, did

it?

And why do

some people have such fascination with the idea of alien life on other planets?

I think it is because they fantasize that if we make contact with other species

in the universe, they will be more mature than we are. They may lead us to a

more peaceful existence. Of course, they might even be worse than we are, or

messed up in different ways. In that case, perhaps human beings may unite in

defense against the invader.

What is your

source of hope? In the power of reason to solve problems? In getting back to

nature? In the basic goodness of humanity? Some new technology that will allow

us to live forever? Or an alien race swooping down from space and teaching us

their ways?

The

people that walked in darkness

have

seen a great light;

and

for those who dwelt in a land of deep darkness,

upon

them light has dawned.

The

Scriptures give a different answer to the question of hope. In the book of Isaiah

the prophet God promises a restoration for the people of God. God’s act of

salvation is depicted as an enlightenment: a new dawn which lifts the

people out of spiritual and moral darkness.

After Jesus’

earthly life, death, and resurrection, the Gospel writer Matthew looked back

several hundred years at the words of the prophet and read them in a new light.

In the ministry of Jesus in Galilee he saw God fulfilling his ancient promise:

in the land once lived in by the descendants of the Israelite tribes of Zebulun

and Napthali, a new sun was rising: a light to reveal God to the nations and

the glory of God’s people Israel.

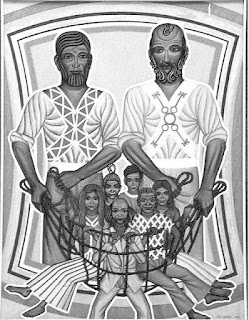

Jesus is light for those who dwell in

darkness. He is hope for us – in our personal lives, in our life in the world,

for humanity is a whole. For each one of us, he is hope for forgiveness of sins

and for living in relationship with others; for healing and peace. For the

world he is a sign of unity and brotherhood; that all people can be one and may

be one. He is the destiny of humankind, that all might come within the reach of

his embrace.

Before it was a European philosophical

movement of the 16th and 17th centuries, ‘enlightenment’

was a word associated with baptism. In several weeks we will, from the Gospel

of John, hear the story of the man born blind, which to the ancient church was

a symbol of baptism, the dawning of the light upon those who could not see.

Yet we may ask one more question: if Jesus

is the light which dispels darkness, why then does there seem to be so much

darkness in ourselves and in the Church and the world? Why, having received the

Gospel, did the congregation in Corinth fall into division and factionalism?

Why do we still deal with lack of unity in the Church? We are in what is known as the Week of Prayer

for Christian Unity, which hardly anyone ever observes any more, not because

there is no need for it. Certainly it might seem to some that enlightenment has

not come, that the one who brings people together is not Jesus, simply because

we must still pray for light and peace and strive for justice and order.

But if we remember that the light Jesus brings is not a dominating light, not a power which forces everyone into its embrace, but an inviting beacon, a power which heals and does no violence, we begin to understand. We see that the first thing Jesus does in his ministry is manifestly unreasonable – he calls uneducated fishermen to share in his ministry to the nations. Certainly a reasonable person interested in changing the world would have chosen others. Yet he chooses them – with all their faults and foibles. The way he chooses to change the world and give people hope is by going to the cross; he opts for the seemingly unfruitful path of suffering. But in this way, he brings light to those who dwell in darkness and the shadow of death. As St Paul writes to the Corinthians:

The message about the cross is

foolishness to those who are perishing;

But to us who are being saved it is

the power of God.

Light has come in Jesus, who chose the

unchosen,

Who unites the dis-united,

Who has power without violence,

Who died in order to live,

That we might live in hope

And even in the midst of sin and death

May live as those enlightened

By the rising of his Son.